In 1996, I was the Chief Engineer (Water Supply) in Water and Power Consultancy Services Private Limited (WAPCOS). In the realm of projects like Water Supply and Storm Water Drainage, our proposal was accepted to design rural water supply for selected villages in Hoshiarpur and Patiala districts of Punjab. At that time, I had no previous experience in planning such schemes, but my confidence stemmed from a basic understanding of hydraulics. Our task was relatively straightforward—design a network with tubewells, a rising main, elevated tank, and a distribution system only till the standpost, adhering to norms set by the CPHEEO. However, upon visiting villages, we discovered that many households had developed their micro water supply systems, utilizing motorized pumps. This raised questions about the necessity of standpost-based supply.

In a neighbouring village not on our list but with a standpost-based supply, I witnessed a buffalo cooling under the open tap and a nearby tank for cattle drinking water. It became clear that taxpayers were covering the costs of standpost-based water supply, while households had invested in constructing and maintaining their independent water supply systems. Punjab seemed to approach water supply differently, possibly due to the progressive nature of farmers receiving remittances from family members abroad.

In retrospect, disturbing the existing individually maintained systems might not have been justified. Despite potential water quality concerns, these systems were 100% owned, operated, and maintained by each household.

Summary of Efforts to Provide Drinking Water in India

Let us delve into the Government led efforts in Rural Drinking Water and Sanitation Sector:

- Post-Independence Initiatives (1949-1986): In the early years after independence, efforts were made to address water scarcity in rural areas. The Community Development Program (1952) was followed by the Accelerated Rural Water Supply Program (ARWSP) in 1972 to address the challenges of coverage of rural water supply in India. ARWSP focused to accelerate the coverage of provision of drinking water in rural areas by focusing on infrastructure development and improving access to safe water sources. In 1986, National Drinking Water Mission (1986) was launched with an aim to provide safe drinking water, but progress was limited.

- Acceleration during the 1990s till 2008: The 1990s witnessed increased attention to rural water supply, with the launching of the Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission (1991). Positives of the mission included its emphasis on community participation, aiming to involve local communities in the planning and management of water supply schemes. The mission also focused on technological innovations and the development of appropriate infrastructure to ensure safe drinking water access in rural habitations. Moreover, the RGNDWM played a crucial role in creating awareness about water quality and sanitation, contributing to the overall improvement of public health. However, limitations included disparities in implementation across different regions and states, leading to uneven progress. Challenges related to water contamination and sustainability also persisted, which was one of the reasons to pilot with Demand Driven and Participatory Approaches by Danish International Development Agency (Danida), which implemented Bilateral programs between Governments of India and Denmark. As brought out above, this article draws from learnings by the author during those times.

Among the efforts parallelly made by Government of India and other development agencies a notable contribution has been made to water and sanitation sector by the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA). These included but not limited to the following:

- Infrastructure Development: SSA emphasized the need for improved infrastructure in schools to create a conducive learning environment. This included the provision of basic amenities like toilets and drinking water facilities. By addressing these infrastructure needs, SSA aimed to ensure that schools were equipped with essential amenities for the overall well-being of students.

- Health and Hygiene Promotion: Recognizing the close relationship between health and education, SSA incorporated health and hygiene components into its framework. This involved promoting hygiene practices, including proper handwashing, sanitation, and access to safe drinking water. By fostering a healthy and hygienic environment, SSA aimed to improve the overall health of students and contribute to their attendance and performance in schools.

- Integration with Total Sanitation Campaign (TSC): SSA was integrated with the Total Sanitation Campaign (later merged into the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan) to address sanitation issues comprehensively. This integration ensured a holistic approach to hygiene promotion, including the construction of sanitation facilities and the promotion of safe sanitation practices in both schools and their surrounding communities.

- Community Participation: SSA recognized the importance of community participation in achieving its goals. Communities were encouraged to actively participate in school management and contribute to the maintenance of school infrastructure, including water supply and sanitation facilities. This collaborative approach aimed to ensure the sustainability of these facilities over the long term.

- Impact on Enrolment and Retention: While the primary focus of SSA was on education, the improvement of infrastructure, including water and sanitation facilities, contributed to increased enrolment and retention of students. Families were more likely to send their children to schools with adequate amenities, positively impacting the overall school environment.

- National Rural Drinking Water Program (2009): The National Rural Drinking Water Program (NRDWP), launched in 2009, was a significant initiative by the Government of India to address the challenges of providing safe drinking water to rural areas. The program aimed to ensure the sustainability of water supply systems, improve water quality, and enhance the coverage of safe drinking water across rural habitations.

Key features of the National Rural Drinking Water Program included:

- Infrastructure Development: NRDWP focused on the creation and improvement of rural water supply infrastructure, including the installation of hand pumps, tube wells, and piped water supply systems. The goal was to enhance accessibility to safe drinking water sources for rural communities.

- Water Quality Monitoring: Recognizing the importance of water quality, the program implemented measures for regular monitoring of water sources. This involved testing for contaminants to ensure that the water supplied met the required quality standards.

- Technological Interventions: NRDWP incorporated technological innovations to optimize water supply systems. This included the use of modern techniques for water treatment and distribution, aimed at improving the efficiency and sustainability of rural water supply schemes.

- Capacity Building: The program emphasized the need for capacity building at the community level. Training and awareness programs were conducted to empower local communities in the operation and maintenance of water supply infrastructure, fostering a sense of ownership and sustainability.

- Community Participation: NRDWP encouraged the active involvement of local communities in planning, implementing, and managing water supply projects. This participatory approach aimed to ensure that the water supply systems met the specific needs and preferences of the communities they served.

While the National Rural Drinking Water Program made notable contributions to rural water supply, challenges persisted, including issues related to water quality, geographical disparities, and the need for sustained community engagement. The program laid the groundwork for subsequent initiatives, such as the Jal Jeevan Mission launched in 2019, which continues to build upon and address the evolving challenges in providing safe drinking water to rural areas in India.

National Water Mission

The National Water Mission launched in 2011 has a vison to conserve water, minimize wastage, and ensure its more equitable distribution both across and within states through integrated water resources development and management. The mission aims to promote sustainable water management practices, address the challenges of water scarcity, and enhance water use efficiency to ensure the availability of water for various sectors in the country. The Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (2014): Launched to promote sanitation and cleanliness, Swachh Bharat Abhiyan indirectly contributed to water quality improvement by addressing open defecation and promoting hygiene practices.

The National Water Mission aims to achieve its vision through a comprehensive set of initiatives, including in-village water supply infrastructure, reliable drinking water source development, water transfer for areas facing quantity and quality issues, technological interventions for potable water treatment, retrofitting of existing piped water supply schemes, greywater management, and capacity building for stakeholders.

While these intentions are commendable, it’s worth noting that successful implementation requires more than just governmental resources. Our experiences so far have revealed potential challenges, prompting a closer examination of the feasibility and resource requirements to achieve the mission’s ambitious goals.

Sustainability Plan-A necessity

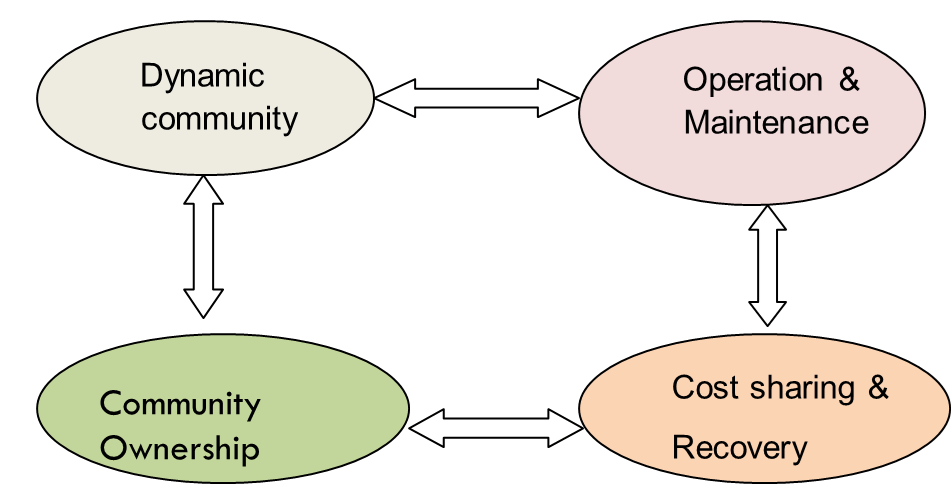

Highlighting the pivotal role of a sustainability plan, especially in alignment with the National Water Mission’s visionary goals, is crucial for ensuring a lasting and reliable water supply for villages. This involves seamlessly integrating sustainability across the entire project lifecycle, including conceptualization, planning, and implementation. Despite the clear intent since the 1990s, there is an ongoing exploration for a practical and cost-effective model to sustain village water supply. In the realm of water-related projects, sustainability goes beyond asset creation, emphasizing a steadfast commitment to robust maintenance practices, which is the hallmark of longevity. Drawing insights from visits to Denmark, where century-old water supply schemes endure with vitality, reveals an imbalance in our approach. Historically, there has been an undue emphasis on asset creation, relegating critical asset maintenance to a secondary status. To address this, we require a paradigm shift in the prevailing mindset which underestimates the capacity of the local government and its bodies to acquire the necessary skills and knowledge to integrate sustainability into conceptualisation and planning. We require models that combine centralised capacities of States Water Supply Departments with localised accountability. For this it is necessary to view maintenance as integral to sustainability. Figure 1 conceptually illustrates how cost sharing and recovery of Operation and maintenance generates an ownership feeling, introduces dynamism in the community to own up operation and maintenance.

Figure 1: Cost sharing/Recovery relationship with ownership, dynamics of community and Operation and Maintenance

Author’s experience in the rural water supply projects emphasize the need for a transformative approach that minimizes capital expenses and prioritizes water conservation. With the National Water Mission’s ambitious objective of ‘Har Ghar Jal-Har Ghar Nal,’ the spotlight must now shift to maintenance and sustainability. Projects serving as instructive pilots can offer valuable lessons for our collective journey towards a water-secure future.

Experience in Water Supply and Sanitation Sector-DANIDA

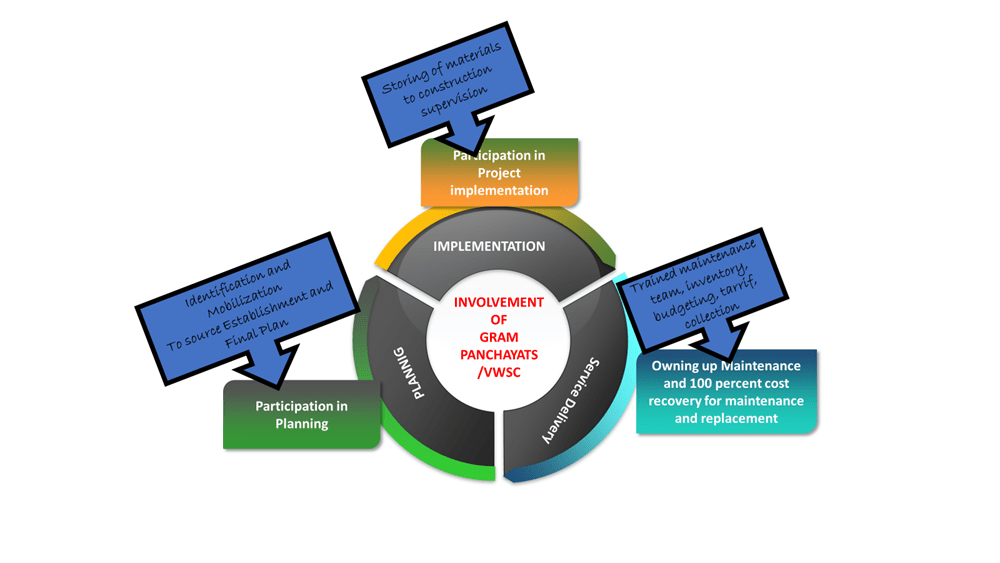

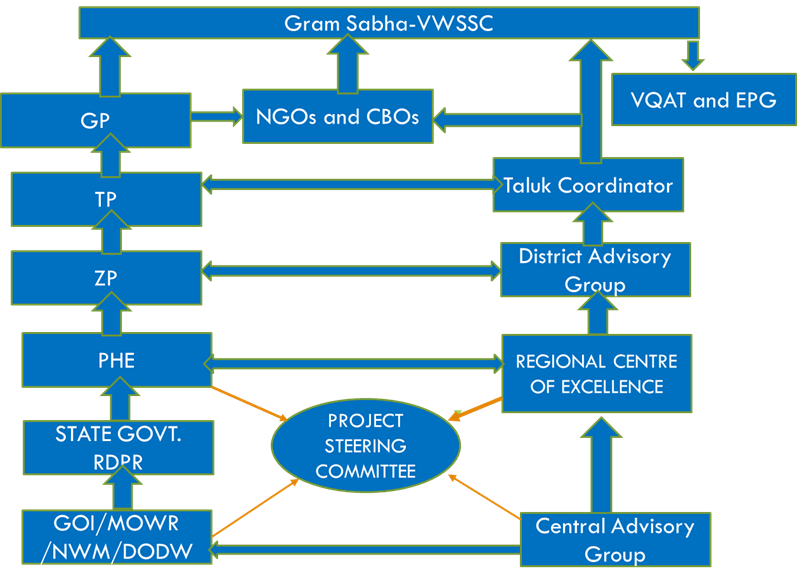

Figure 2: Conceptual Diagram for Involving Village Water and Sanitation Committee

Figure 2 presents a self-explanatory conceptual diagram for involving Gram Panchayats or Local Government through Village Water and Sanitation Committee drawn from author’s experience in Danida assisted schemes implemented during 1997-2005 seamlessly integrated into the regular departmental functions of the Governments of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, respecting their established procedures. In fact, the schemes were strictly implemented by the Government Departments and Garm Panchayat itself with advice and support in enhancement of their capacities by Danida.

Ingredients of Demand Driven and Participatory Approach:

Essential features of demand driven and participatory approach include Participatory Planning, Capital Cost contribution, Capacity Building, Participatory Implementation, Participatory Water Quality Management, Participatory Sanitation and Water Conservation, Development of Local Work force followed by Budgeting, Accounting and Billing for Cost recovery. These are briefly explained below:

Participatory Planning:

The planning process was executed with a habitation-wise approach, employing participatory rural appraisal guided by a sociologist. This involved social mapping, identification of water sources, and joint assessments with the village team. The cost for each habitation was determined on the spot using ready reckoners developed by the technical team. The community was engaged in a trade-off between their aspirations and affordability, akin to family budgeting. The approved scheme then underwent technical sanction by the government.

Capital Cost contribution:

The projects were conceptualized based on a demand-driven and participatory framework. A pivotal element was ensuring the commitment of beneficiaries by requiring them to contribute 1/10th to 1/7th of the assessed cost upfront. This was successfully contributed by the community.

Capacity Building:

Recognizing the necessity of community involvement, innovative approaches were employed to build the capacities of Village Water and Sanitation Committees. This encompassed aspects from procurement to inspection, storage, vigilance, transportation, quality control, and ownership of the scheme. Creative methods such as documentation in the local language, discussions, presentations, and films were utilized.

Participatory Implementation:

Projects were implemented without disrupting government procedures, in collaboration with the community. Active involvement of the community was ensured at every stage.

Participatory Water Quality Management:

Rigorous testing of water for vital parameters was conducted, and communities were informed accordingly. Links were established between water testing facilities and communities for detailed testing when required. Village teams were trained for basic water quality testing for bacterial contamination.

Participatory Sanitation and Water Conservation:

Community engagement was sustained through regular interactions promoting water conservation practices. Initiatives included proper drainage, utilization of drained water for various purposes, and maintaining a clean environment. Rooftop rainwater harvesting systems were introduced in schools and community toilets, involving school children in their management.

Local Work Force:

A local work force of mechanics, electricians and plumbers was professionally trained for each habitation to deal with any breakdowns.

Budgeting, Accounting and Billing:

Empowering the community as the ultimate owners, Village Water and Sanitation Committees were trained in developing annual maintenance budgets. Monthly billing was based on these budgets, ensuring financial sustainability.

These principles were successfully applied in water supply schemes across Cuddalore and Vilupuram districts in Tamil Nadu and Kolar, Chitradurga, and Bijapur districts in Karnataka, resulting in well-functioning and sustainable projects between the year 1997-2005.

Adopting Above Principles in Jal Jeevan Mission

State Governments Drinking Water Supply Departments (Former Public Health Departments)- Modus Operandi:

The State Government run Drinking Water Supply Departments or the Public Health Departments have hitherto pursued a Clientelist Model serving the dictates of Politicians. This inherently implies capital creation focus with Government funding with a capital creation focus, high cost high staffing ratio and very low cost recovery. This model of development provides water supply infrastructure, provides employment leading to high staffing and maintenance costs, a small fraction of which might be recovered with artificially depressed tariffs. Despite the noble intent expressed in the Jal Jeevan Mission to provide ‘safe water’ to every village household by 2024, systems haven’t been developed to obviate the possibility of bacterial contamination. Further, there is a possibility of inadequate guard against cost escalation and spreading the resources thin which effects the reliability of water supply and restricts it to a few hours each day. The absence of pressure in waterlines during major part of the day enhances the chances of bacterial contamination. In cities, people invest on water purifiers to deal with this issue but in villages it becomes difficult for every house to invest on these implements and even if they did it, it would not be possible to maintain them at the village level. This leads to uncared for defunct schemes, unreliable water supply and increased risk of bacterial water contamination.

Learning from the Pilot Projects

As explained in the foregoing, during my years with Danish International Development Agency (Danida), defunct water supply schemes at village level was a common sight which is why Danish assistance concentrated on rehabilitation and augmentation of the existing infrastructure wherever it existed but with complete involvement of the community right from conceptualisation to implementation before finally transferring the scheme to the users with adequate building up of the local capacities in all aspects of operation and maintenance of water supply schemes through the Gram Panchayats.

Proposed Institutional Structure and Responsibilities:

As previously highlighted, the envisioned institutional framework harnesses the strengths of both the Government and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) to foster local capacities for the autonomous maintenance and sustainability of water supply schemes. A critical distinction lies in the extensive involvement of the community across the conceptualization, implementation, and quality control phases in pilot projects. However, the widespread implementation of the Jal Jeevan Mission may encounter a potential shortfall in achieving complete community engagement, despite the articulated intent. Consequently, there is a looming risk of insufficient maintenance due to a dearth of financial resources and the absence of a credible institutional structure, thereby jeopardizing the objective of providing a safe and sustained water supply. Nonetheless, initiating these efforts as early as possible is imperative for the effective functioning of water supply schemes throughout their entire lifespan.

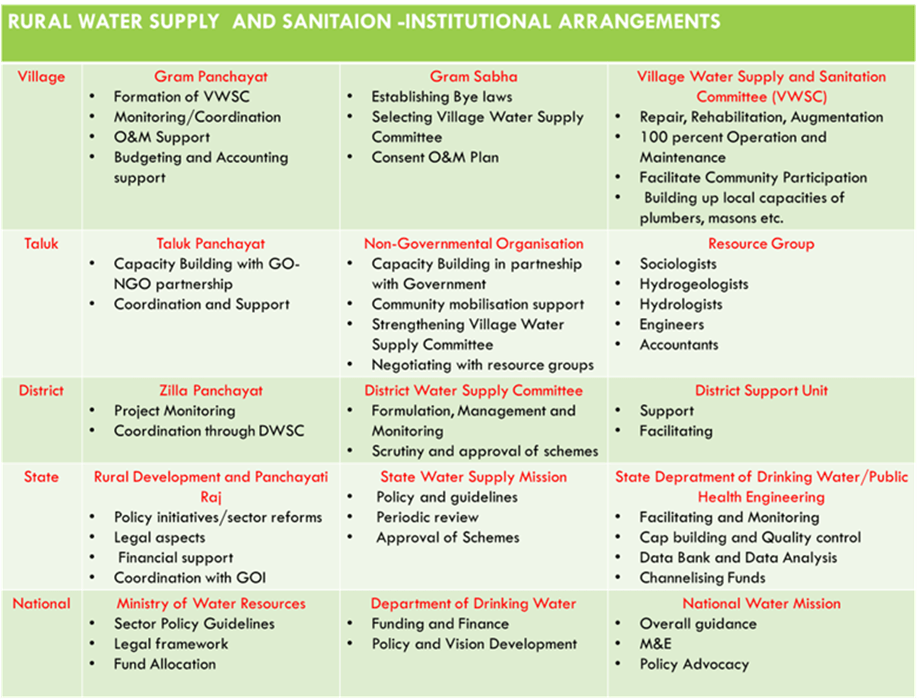

Table 1 below outlines the suggested roles at the National, State, District, Taluk, and Village Levels, with the Panchayati Raj Department assuming a pivotal role in ensuring assured, sustained, and safe water supply to the village community. The department engages in a credible Government-NGO partnership at the Taluk and Gram Panchayat Levels, playing a crucial role in developing local resources for the operation, maintenance, and cost recovery of constructed water supply schemes.

Table 1: Suggested Roles at each Level for Sustainability of Jal Jeevan Mission

Challenges:

The initiative faces several significant challenges, as anticipated by me, including:

- Inertia of Government Departments: Overcoming bureaucratic inertia within government departments is a critical hurdle.

- Mobilizing the Community: A potential time lag in initiating community mobilization poses a challenge in gaining community participation.

- Inadequate Capacity of NGOs and CBOs: Limited capacity within Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) is identified as another obstacle.

Despite these challenges, establishing credible capacity-building measures for resources is viable through innovative training approaches for the local workforce. This includes the development of training materials in the local language, complemented by visual aids, requiring persistent efforts by a reliable Government-NGO partnership.

The objective is to delegate the day-to-day management, repairs, maintenance, budgeting, accounting, billing, and collection of all water supply functions to the Gram Panchayat level. Concurrently, capacity-building efforts aim to achieve similar competencies at the levels of Taluk Panchayat and Zilla Panchayat.

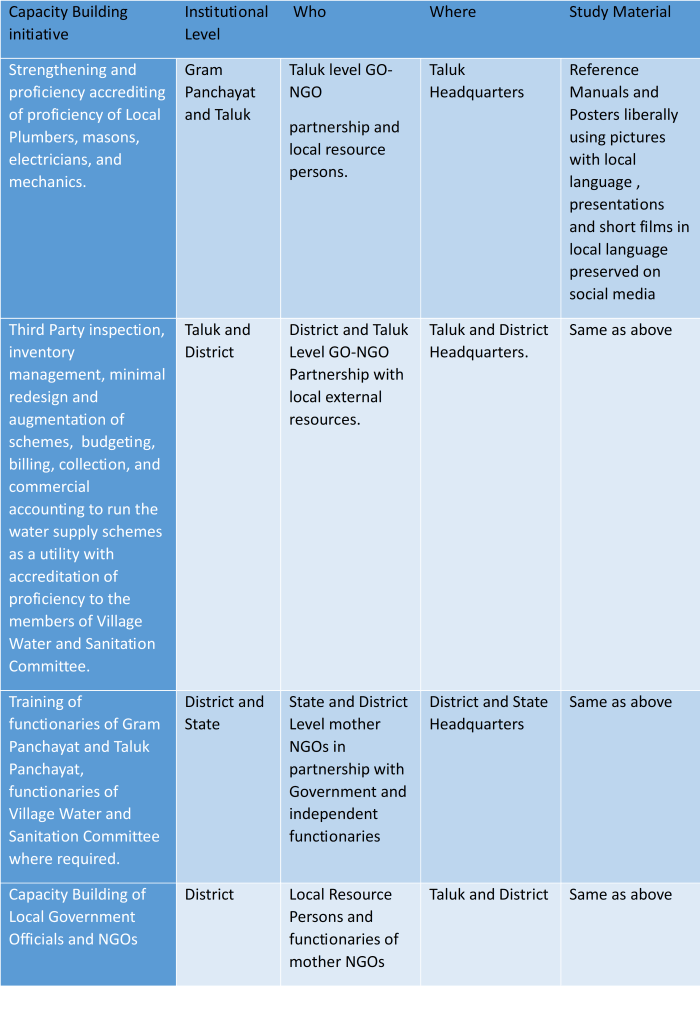

Table 2 below outlines a comprehensive Capacity Building Action Plan, acknowledging the potential time lag in initiating the initiative. Despite this delay, it is anticipated that enthusiastic and motivated local NGO officials will play a crucial role in encouraging community ownership and the effective operation of water supply schemes.

Table 2: Strategic Capacity Building

Figure 3: Jal Jeevan Mission- Sustainable Operation and Maintenance-Proposed Institutional Structure

Conclusion

In conclusion, the development of rural water supply and sustainability has been a contemplative journey, marked by the assimilation of lessons learned and the confrontation of challenges. As we navigate the intricate landscape of water projects, it becomes clear that our unwavering commitment to efficiency and sustainability is of paramount importance. The shared experiences, spanning from the early stages of project design in Punjab to the collaborative efforts with DANIDA, underscore the necessity for a comprehensive vision.

This blog illuminates the transformative potential inherent in demand-driven and participatory approaches, placing a strong emphasis on community engagement at every stage. The success stories from Tamil Nadu and Karnataka stand as guiding lights, showcasing a path where local ownership, meticulous planning, and innovative capacity building converge to create not merely water supply systems but enduring community assets.

As the National Water Mission propels us forward with its ambitious vision of ‘Har Ghar Jal-Har Ghar Nal,’ it is imperative to refocus our attention on the twin pillars of maintenance and sustainability. The Danish model, with its proactive leak control and long-term asset management emphasis, offers a paradigm worth adopting.

By embracing a mindset shift, elevating the value of maintenance, and placing community participation at the core, we can ensure that today’s water projects continue to flow, robust and resilient, for generations to come. The journey toward water security is ongoing, and the projects discussed herein stand as instructive pilots, providing insights and inspiration for a water-secure future. Let us not merely construct projects but nurture them, fostering a legacy of sustainable water management for the prosperity of all.