In 1996, I was the Chief Engineer (Water Supply) in Water and Power Consultancy Services (India) Ltd. (WAPCOS). In the realm of projects like Water Supply and Storm Water Drainage, our proposal was accepted to design rural water supply for selected villages in Hoshiarpur and Patiala districts of Punjab. At that time, I had no previous experience in planning such schemes, but my confidence stemmed from a basic understanding of hydraulics. Our task was relatively straightforward—design a network with tubewells, a rising main, elevated tank, and a distribution system only till the standpost, adhering to norms set by the CPHEEO. However, upon visiting villages, we discovered that many households had developed their micro water supply systems, utilizing motorized pumps. This raised questions about the necessity of standpost-based supply.

In a neighbouring village not on our list but with a standpost-based supply, I witnessed a buffalo cooling under the open tap and a nearby tank for cattle drinking water. It became clear that taxpayers were covering the costs of standpost-based water supply, while households had invested in constructing and maintaining their independent water supply systems. Punjab seemed to approach water supply differently, possibly due to the progressive nature of farmers receiving remittances from family members abroad.

In retrospect, disturbing the existing individually maintained systems might not have been justified. Despite potential water quality concerns, these systems were 100% owned, operated, and maintained by each household.

National Water Mission

We have come a long way since 1996, the National Water Mission launched in 2011 has a vison to conserve water, minimize wastage, and ensure its more equitable distribution both across and within states through integrated water resources development and management. The mission aims to promote sustainable water management practices, address the challenges of water scarcity, and enhance water use efficiency to ensure the availability of water for various sectors in the country.

The National Water Mission aims to achieve its vision through a comprehensive set of initiatives, including in-village water supply infrastructure, reliable drinking water source development, water transfer for areas facing quantity and quality issues, technological interventions for potable water treatment, retrofitting of existing piped water supply schemes, greywater management, and capacity building for stakeholders.

While these intentions are commendable, it’s worth noting that successful implementation requires more than just governmental resources. Our experiences so far have revealed potential challenges, prompting a closer examination of the feasibility and resource requirements to achieve the mission’s ambitious goals.”

Sustainability Plan-A necessity

The importance of a sustainability plan cannot be overstated, especially when aligned with the visionary goals set forth by the National Water Mission. A comprehensive water resources conservation plan, intricately woven into project planning, should be deemed indispensable. Regrettably, it appears that this essential aspect of sustainability has not been explicitly emphasized, as no Government Department has expressly solicited our consultation to integrate sustainability considerations into planning procedures.

In the realm of water-related projects, sustainability extends beyond the mere creation of assets; it necessitates a steadfast commitment to robust maintenance practices. The longevity of a developed scheme, coupled with adequate cost recovery from end-users, stands as the hallmark of sustainability. Drawing insights from my visits to Denmark, where century-old water supply schemes endure with vitality, I am compelled to acknowledge a prevailing imbalance in our approach. Historically, there has been an undue emphasis on asset creation, while the critical facet of asset maintenance has been relegated to a secondary status.

Maintenance, often perceived as a laborious and underappreciated task by many engineers, demands a paradigm shift in our collective mindset. The absence of routine surveys to proactively identify vulnerabilities such as cracks and fractures in pipes and valves is a significant lapse. Astonishingly, a substantial 30-40 percent of water leaks underground or seeps into the surrounding soil before reaching its intended consumers. In contrast, Danish engineers prioritize leak control, with an admirable target of maintaining distribution losses below ten to fifteen percent.

Reflecting on these disparities prompts a vital question: are we genuinely committed to water conservation? Sharing insights from my personal experiences in rural water supply, where I integrated elements, such as minimizing capital expenses and emphasizing water conservation, underscores the need for a transformative approach. While Danish assistance to India may not have primarily involved financial contributions, the focus has consistently been on fostering impactful learning experiences.

As our National Water Mission (Now Jal Jeevan Mission) surges ahead with the ambitious objective of ‘Har Ghar Jal-Har Ghar Nal’ (Water to every house and a water tap in every house), the spotlight must now shift to the critical facets of maintenance and sustainability. The projects I have been involved in could serve as instructive pilot projects, offering valuable lessons that can inform our collective journey towards a water-secure future.

Experience in Water Supply and Sanitation Sector-DANIDA

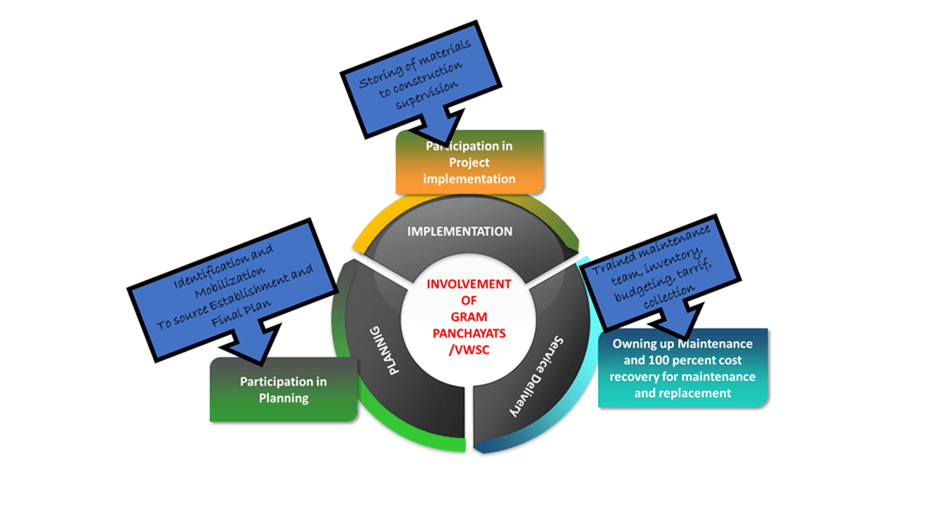

Figure: Conceptual Diagram

Upon joining the Royal Danish Embassy, I was entrusted with the coordination of bilaterally assisted projects in the Water Sector under the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA). It was during this tenure that I gained valuable insights into the Danish approach, characterized by a Demand-Driven and Participatory Basis for providing assistance. Notably, these schemes were seamlessly integrated into the regular departmental functions of the Governments of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, respecting their established procedures.

Demand Driven and Participatory Approach:

The projects were conceptualized based on a demand-driven and participatory framework. A pivotal element was ensuring the commitment of beneficiaries by requiring them to contribute 1/10th to 1/7th of the assessed cost upfront.

Participatory Planning:

The planning process was executed with a habitation-wise approach, employing participatory rural appraisal guided by a sociologist. This involved social mapping, identification of water sources, and joint assessments with the village team. The cost for each habitation was determined on the spot using ready reckoners developed by the technical team. The community was engaged in a trade-off between their aspirations and affordability, akin to family budgeting. The approved scheme then underwent technical sanction by the government.

Capacity Building:

Recognizing the necessity of community involvement, innovative approaches were employed to build the capacities of Village Water and Sanitation Committees. This encompassed aspects from procurement to inspection, storage, vigilance, transportation, quality control, and ownership of the scheme. Creative methods such as documentation in the local language, discussions, presentations, and films were utilized.

Participatory Implementation:

Projects were implemented without disrupting government procedures, in collaboration with the community. Active involvement of the community was ensured at every stage.

Potable Water Quality:

Rigorous testing of water for vital parameters was conducted, and communities were informed accordingly. Links were established between water testing facilities and communities for detailed testing when required. Village teams were trained for basic water quality testing for bacterial contamination.

Sanitation and Water Conservation:

Community engagement was sustained through regular interactions promoting water conservation practices. Initiatives included proper drainage, utilization of drained water for various purposes, and maintaining a clean environment. Rooftop rainwater harvesting systems were introduced in schools and community toilets, involving school children in their management.

Local Work Force:

A local work force of mechanics, electricians and plumbers was professionally trained for each habitation to deal with any breakdowns.

Budgeting, Accounting and Billing:

Empowering the community as the ultimate owners, Village Water and Sanitation Committees were trained in developing annual maintenance budgets. Monthly billing was based on these budgets, ensuring financial sustainability.

These principles were successfully applied in water supply schemes across Cuddalore and Vilupuram districts in Tamil Nadu and Kolar, Chitradurga, and Bijapur districts in Karnataka, resulting in well-functioning and sustainable projects.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the journey through rural water supply and sustainability has been a reflective exploration of lessons learned and challenges faced. As we navigate the intricate landscape of water projects, it becomes evident that our commitment to efficiency and sustainability is paramount. The experiences shared, from the early days of project design in Punjab to the nuanced approach adopted in collaboration with DANIDA, underscore the need for a holistic vision.

The blog sheds light on the transformative potential embedded in demand-driven and participatory approaches, emphasizing community engagement at every stage. The success stories from Tamil Nadu and Karnataka serve as beacons, illuminating a path where local ownership, meticulous planning, and innovative capacity building converge to create not just water supply systems but enduring community assets.

As the National Water Mission propels us forward with its ambitious vision of ‘Har Ghar Jal-Har Ghar Nal,’ it is crucial to redirect our focus onto the twin pillars of maintenance and sustainability. The Danish model, with its emphasis on proactive leak control and long-term asset management, presents a paradigm worth adopting.

In embracing a mindset shift, where the value of maintenance is elevated and community participation is at the core, we can ensure that the water projects of today continue to flow, robust and resilient, for generations to come. The journey towards water security is ongoing, and the projects discussed herein stand as instructive pilots, offering insights and inspiration for a water-secure future. Let us not merely construct projects but nurture them, fostering a legacy of sustainable water management for the prosperity of all.